How the U.S. Dollar Has Moved Under Each President, and What It Means for the Global Economy

How the U.S. Dollar Has Moved Under Each President — and What It Means for the Global Economy

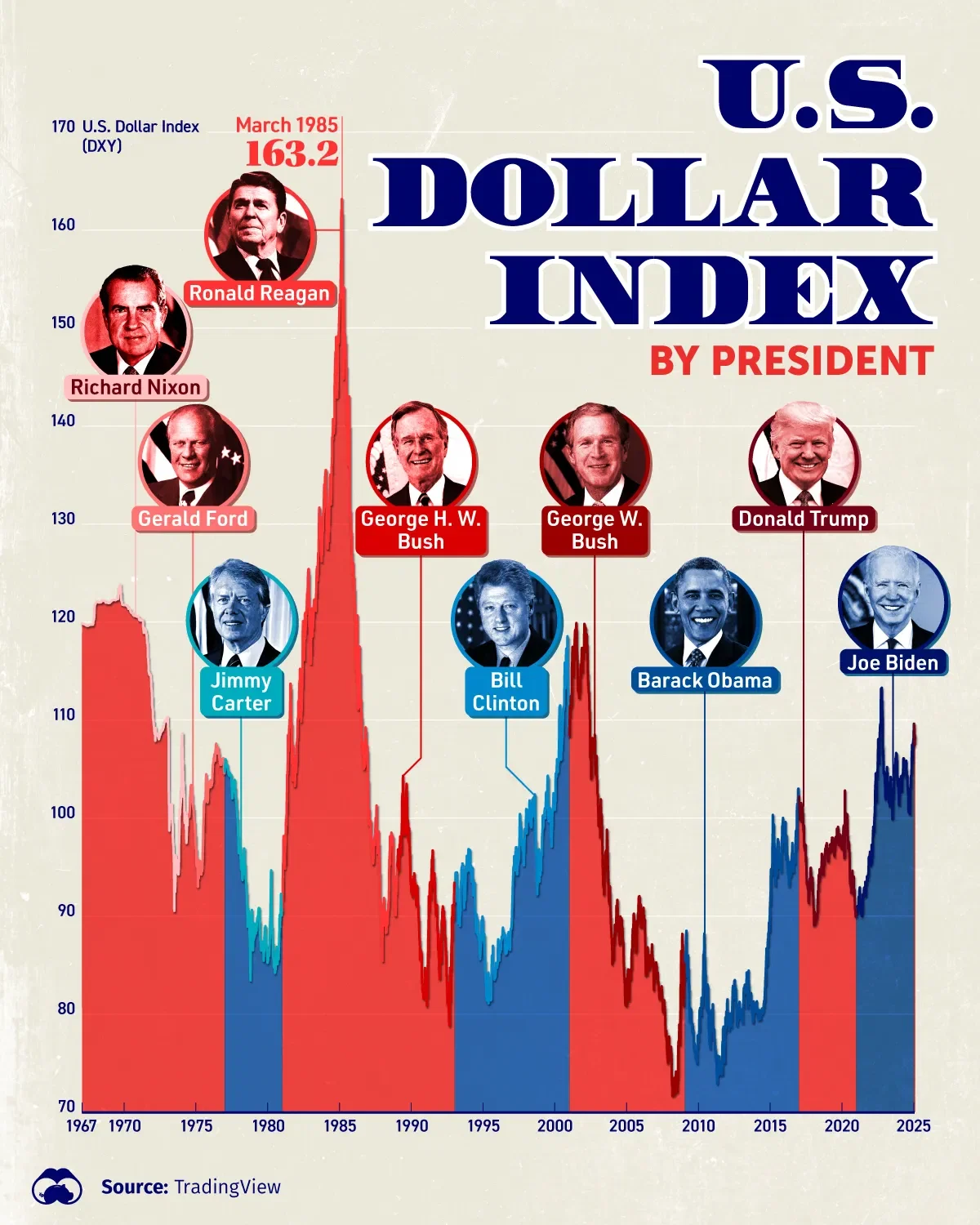

The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) measures the dollar’s value against six major currencies (the euro, yen, pound, Canadian dollar, Swedish krona, and Swiss franc). Since its creation in 1973 (base value 100), the DXY has seen dramatic cycles – climbing to a record high of ~164.7 in 1985 and plunging to an all-time low around 70.7 in early 2008. These swings have often coincided with different U.S. presidencies and global economic phases. Below, we examine how the dollar fared under each president from Ronald Reagan through Donald Trump, and discuss what a strong or weak dollar means for trade, inflation, commodities, and emerging markets. We’ll also consider the current environment in late 2025, where a softer dollar is easing pressures globally.

DXY Performance by Presidential Term (1981–2021)

Each president’s tenure saw the dollar index start and end at different levels. The table below shows the DXY at the start vs. end of each presidency from 1981 onward, and the percentage change over the term:

This historical data reveals a pattern: since the late 1980s, the dollar tended to weaken by the end of Republican presidencies and strengthen by the end of Democratic ones. For example, the DXY fell about 5% under George H.W. Bush, 25% under George W. Bush, and 10% under Trump – but it rose ~22% under Clinton and ~18% under Obama. Reagan’s tenure was an exception in that the dollar ended roughly flat despite major volatility in between. What drove these moves? Below we put each period in context.

Early–Mid 1980s (Reagan): Volcker’s Rate Hikes and the Plaza Accord

When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the U.S. was battling high inflation. Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker had aggressively raised interest rates to nearly 20%, driving a surge in the dollar’s value. In fact, the DXY ascended to a record peak in March 1985 under Reagan’s watch. A strong dollar made imports cheaper for Americans but hurt U.S. export competitiveness, contributing to trade deficits. Concerned that the dollar was too strong, U.S. officials and major allies struck the Plaza Accord in September 1985 to coordinate a dollar depreciation. The agreement worked: by the end of Reagan’s second term, the DXY had fallen sharply from its mid-80s heights (dropping from ~160 back to the 90s). Reagan’s presidency thus saw a full round trip for the dollar – soaring early on and then plunging after 1985, ultimately ending about where it started.

George H.W. Bush continued this trajectory. The dollar remained relatively weak through 1989–1992 as the effects of the Plaza Accord lingered. By Bush’s last year, the DXY hovered in the low-90s. The weaker dollar of the late ’80s aided U.S. exporters and helped shrink the trade deficits that had ballooned earlier in the decade. However, a lower dollar also meant higher import prices, which along with rising oil costs contributed to inflationary pressure in the early 1990s recession. Overall, the Reagan and Bush Sr. years demonstrated the dollar’s sensitivity to interest rate policy and global coordination: Volcker’s tight money drove it up, and the Plaza Accord drove it back down.

1990s (Clinton): “Strong Dollar” Policy and the Tech Boom

By the early 1990s, the dollar was coming off its post-Plaza lows. Under President Bill Clinton (1993–2001), the U.S. embraced a “strong dollar is in our interest” mantra (voiced by Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin), signaling that a robust currency was a policy goal. Several factors powered the dollar’s 20% climb during Clinton’s tenure. First, the U.S. economy enjoyed a boom in the late 1990s – fueled by the tech boom and productivity gains – which attracted investment into U.S. assets and increased demand for dollars. Second, the government moved from deficits to budget surpluses by the end of the decade, bolstering confidence in the U.S. fiscal position. The DXY, which had languished around ~85 in 1995, rallied to over 110 by 2000.

Notably, the 1997 Asian financial crisis and 1998 Russian default prompted a “flight to quality” that benefited the U.S. dollar as a safe haven. The combination of strong growth at home and turmoil abroad made the dollar “king” of currencies in the late ’90s. By Clinton’s last days, the dollar index was near its highest levels since the mid-1980s.

2000s (G.W. Bush): Deficits, Crisis, and an All-Time Low Dollar

The dollar’s fortunes reversed under George W. Bush (2001–2009). Early in Bush’s term, the DXY remained elevated (it spiked above 117 after 9/11). But soon a steep decline set in. A few key forces drove the dollar down ~25% over Bush’s eight years:

- Monetary Policy: In the early 2000s, the Fed cut interest rates aggressively to combat recession and the tech bubble bust. Lower U.S. rates reduced the dollar’s yield appeal. Later, from 2004–2006, the Fed did raise rates, but by then twin deficits were dominating the narrative.

- Twin Deficits: The U.S. federal budget swung back into deficit due to tax cuts and spending (including wars in Afghanistan and Iraq), and the current account deficit (trade gap) widened. These imbalances weakened investor confidence in the dollar. By 2007, the U.S. was running large trade deficits financed by foreign capital – a scenario often linked to a weaker currency over time.

- Global Financial Crisis: The dollar plunged to its all-time low in March 2008 (DXY ~70.7) amid the global financial meltdown. This was partly due to the Federal Reserve’s emergency interest rate cuts and quantitative easing, which flooded the system with dollars. Although the 2008 crisis initially sparked a rush to dollars (a safe-haven spike in late 2008, reflected in DXY bouncing back above 80 by year-end), the overall trend of Bush’s presidency was dollar weakness. From start to finish, the DXY went from roughly 112 to 84 – the dollar’s worst performance under any modern president.

The weak dollar in the 2000s had mixed effects. It boosted U.S. export competitiveness, helping some manufacturing and agricultural sectors. Indeed, by 2007–2008, U.S. exports were a bright spot in the economy. However, the flip side was higher import prices, which contributed to inflation in commodities (like oil surging to record highs in 2008). Emerging markets that had borrowed in dollars also felt pain as the dollar’s decline was accompanied by global credit stress.

2009–2016 (Obama): Recovery and a Resurgent Dollar

Barack Obama inherited a dollar near multi-decade lows in 2009, amidst a global recession. In the first few years of Obama’s term, the Federal Reserve undertook massive quantitative easing (QE) to revive growth. Intuitively, money-printing might weaken a currency – and indeed the DXY stayed relatively soft through 2011–2012 (in the high-70s to low-80s range). But as the U.S. economy began to recover ahead of other advanced economies, the dollar found a floor. The Fed signaled an end to QE and eventual rate hikes by 2013, while Europe and Japan were still easing aggressively. This divergence set the stage for a dollar rally.

From 2014 to 2016, the DXY surged from about 80 to over 100. In fact, by 2016 the index hit ~102 – its highest in 13 years. The drivers were clear: the Fed started raising interest rates (lift-off in late 2015) as the U.S. labor market strengthened, even as the ECB and Bank of Japan were pushing rates down. Higher U.S. yields attracted global investors, strengthening the dollar (a classic case where the prospect of tighter U.S. monetary policy boosts the currency). Obama’s term thus ended with the dollar about 18% stronger than at inception.

This stronger dollar had the expected effects: cheaper imports for Americans (keeping a lid on inflation) but weighing on U.S. exporters and multinationals’ foreign earnings. Notably, emerging markets felt pressure during the mid-2010s dollar upturn – countries with dollar-denominated debts (and commodities priced in dollars) struggled as the USD climbed.

2017–2020 (Trump): Trade Wars, Tax Cuts, and Volatility

Donald Trump’s presidency saw the dollar seesaw and ultimately decline by roughly 10%. In early 2017, the dollar index was around 100 – buoyed by a post-2016 election surge on expectations of tax cuts and infrastructure spending. However, despite solid U.S. growth in 2017–2019 and Fed rate hikes through 2018, the dollar did not rise further; in fact it drifted lower in 2017 to ~92. One reason was that Trump’s Treasury at times talked in favor of a weaker dollar to boost U.S. exports. Additionally, trade policy uncertainty began to weigh on the greenback: in 2018, the Trump administration imposed tariffs on major trading partners (China, Europe, etc.). While tariffs themselves can create inflation (by raising import costs) and potentially prompt tighter Fed policy, they also introduced global growth risks that dampened investor appetite for U.S. assets. The net effect was a mixed one for the dollar. The DXY did firm up in 2018–2019 (oscillating in the mid-90s) as the Fed’s continued rate hikes and relative U.S. economic strength provided support.

The pandemic shock in 2020 then dramatically altered the picture. In March 2020, when COVID-19 panic set in, the dollar spiked briefly (investors rushed into USD cash), but the Federal Reserve’s emergency response – slashing rates to zero and unleashing trillions in liquidity – soon caused the dollar to plummet. By the end of 2020 and into January 2021, the DXY fell below 90, hitting its weakest level in over two years. This was a fitting bookend for Trump’s term: despite periods of dollar strength, ultimately the massive stimulus and low rates needed to fight COVID resulted in a significantly softer dollar by the time Trump left office.

It’s worth noting that Trump often publicly lamented a strong dollar (arguing it hurt U.S. manufacturing). In that sense, the weaker dollar in 2020 was aligned with his stated preference. However, it also reflected severe economic turmoil. U.S. import prices were rising by late 2020 (partly due to the weaker dollar and supply chain issues), contributing to inflation pressures that would fully emerge in 2021.

2021–2025 (Biden): Tightening Cycle and Dollar Peak

When Joe Biden took office, the dollar index hovered near 90 — its weakest level in years after the pandemic stimulus and ultra-low rates. But surging inflation quickly changed the landscape. In 2022, the Federal Reserve launched its fastest rate-hiking cycle since the 1980s, sending the DXY to a 20-year high near 114.

That spike in dollar strength tightened global financial conditions, squeezed emerging-market currencies, and briefly softened commodity prices. By 2023, as inflation began to cool and the Fed paused rate hikes, the dollar started to ease into the 105–108 range, stabilising through 2024.

- U.S. growth remained resilient, supported by domestic investment and clean-energy policy under the Inflation Reduction Act.

- Commodity prices rebounded as the dollar weakened, helping miners and exporters.

- Emerging markets saw relief as debt servicing costs in USD fell and capital inflows resumed.

By the end of Biden’s term, the dollar was up roughly 19 % overall — stronger than when he took office but well off its 2022 highs. The greenback’s moderation helped rebalance global trade and set the stage for a softer cycle as Trump returned to the White House in 2025.

.png)

Why Dollar Strength vs. Weakness Matters

A rising or falling dollar isn’t just a Wall Street curiosity – it has real impacts on the global economy. Here are four key areas influenced by U.S. dollar moves:

- Trade Competitiveness: The dollar’s value directly affects trade. When the USD is strong, U.S. exports become more expensive abroad and less competitive, while imports become cheaper for Americans. This tends to widen the U.S. trade deficit – a boon for U.S. consumers (who enjoy lower prices on imported goods or a cheap vacation overseas), but a headwind for American manufacturers and farmers exporting their products. Conversely, a weaker dollar makes U.S. exports more competitive (foreign buyers get more dollars per their currency) and imports pricier. A strong dollar is thus “a blessing for American consumers… but a bane for… Americans looking for a future job in manufacturing” (brookings.edu). For example, during strong-dollar periods, industries like aerospace or tech may struggle to sell abroad, whereas a dollar decline can boost those sectors’ global sales.

- Inflation and Import Costs: Currency swings feed into inflation through import prices. A stronger dollar tends to hold down U.S. inflation – fewer dollars are needed to buy the same foreign goods (bls.gov). This was evident in the late 1990s and 2010s when a strong dollar helped keep consumer prices in check. On the other hand, a weaker dollar can stoke inflation by raising the cost of imported items (from electronics to clothing to raw materials). For instance, when the dollar fell in the 2000s, Americans saw higher prices for imported oil, contributing to painful gas price spikes. Essentially, dollar appreciation is like a price cut for imports, while depreciation is a price hike. Central banks, including the Fed, monitor the dollar’s exchange rate as one factor in the inflation outlook.

- Commodity Prices (Oil & Gold): Global commodities are mostly priced in U.S. dollars, so the dollar’s strength often has an inverse relationship with commodity prices (en.wikipedia.org). When the dollar falls, commodities tend to rise (in USD terms), and vice versa. A weaker dollar gives buyers using other currencies more purchasing power, boosting demand for commodities and pushing prices up. This dynamic is commonly seen with oil and gold: a dropping dollar frequently coincides with rallies in oil and gold prices (advisorperspectives.com). For example, during 2020’s dollar downturn, gold prices hit record highs as investors sought inflation hedges. Emerging economies that export commodities benefit from a cheaper dollar because it usually means higher global commodity prices in dollar terms, improving their export revenues (en.wikipedia.org). On the flip side, when the dollar surges (as in 2022), it often pressures commodity prices downward, since commodities become more expensive in other currencies, hurting demand. (It’s no coincidence that oil prices often ease when the dollar is very strong.)

- Emerging Market Liquidity and Debt: Many emerging market (EM) countries borrow in U.S. dollars and rely on dollar funding. A strong dollar can be very painful for them. Here’s why: when the dollar rises, EM currencies fall in value, making debt payments in dollars more expensive in local-currency terms. A prime example was the 2013 “taper tantrum” and the late-2010s, when a stronger USD hurt countries like Turkey, Argentina, and others with large dollar debts. Dollar appreciation also tends to raise global interest rates and reduce capital flows to EMs, as investors prefer dollar assets. In contrast, a weaker dollar loosens financial conditions for EMs. It often correlates with lower global interest rates and investors hunting for yield in emerging markets. When the USD declines, EM borrowers find it cheaper to service debt, and they often see renewed foreign investment. Additionally, because a softer dollar usually boosts commodity prices, commodity-exporting EM nations get a revenue windfall, improving their fiscal and growth prospects. In short, a strong dollar can drain liquidity from emerging economies (and has even contributed to past EM crises), whereas a weak dollar is like a relief valve that can spur growth in developing countries. This cyclicality is sometimes called the “Dollar Smile” or dollar cycle in EM growth.

2025 Lens: A Softer Dollar Eases Global Strains

Fast-forward to today: in 2022, the dollar surged to its highest level in 20 years (DXY peaked around 114) amid aggressive Fed rate hikes and geopolitical turmoil. This dollar strength in 2022 contributed to imported inflation pressures worldwide (especially for countries that import energy) and squeezed many emerging markets. However, in 2023 the trend reversed – as U.S. inflation cooled and the Fed paused tightening, the dollar index fell back into the 100–102 range by year-end. In 2024 and into October 2025, the dollar has remained off its highs, fluctuating in the high-90s rather than above 110.

This recent USD weakness is providing breathing room for the global economy. Notably, softer dollar conditions support commodity prices and global trade. Oil prices, for instance, have been relatively elevated in 2023–2025 partly because a cheaper dollar boosts demand (though other factors like OPEC’s supply cuts also play a role). A weaker dollar also eases the debt burden on emerging markets – indeed, several EM countries that struggled when the dollar was rampant in 2022 have seen their currencies stabilize, allowing their central banks to cut interest rates without crashing their exchange rates.

From a macro perspective, the dollar’s retreat is generally constructive for world growth. It reduces imported inflation for Europe, Japan, and others (since the dollar-priced surge in commodities has moderated), and it improves financial stability in developing nations. In the U.S., a slightly weaker dollar can actually be welcome news for manufacturers and exporters, who become more competitive abroad. Federal Reserve officials have noted that the dollar’s pullback in 2023 helped alleviate some inflation on imports and might reduce the need for further rate hikes.

Of course, the balance is delicate. If the dollar were to slide too far, it could spook markets or fuel excessive commodity inflation. But as of late 2025, we are seeing a healthy correction from extreme dollar strength. The greenback is still strong by long-term standards, but not stranglingly so. This middle ground – where the dollar is stable-to-gently weaker – is often a sweet spot for the global economy: trade flows improve, commodity exporters earn more, and borrowers in poorer countries breathe easier.

Bottom line: The U.S. dollar’s ups and downs under different presidents have taught us that policy choices, interest rates, and global events can all sway the currency. A strong dollar tends to favor U.S. consumers and keep inflation low, but can hurt exports and emerging economies. A weak dollar boosts U.S. competitiveness and global liquidity, but raises import costs and can spur inflation. Today’s backdrop of a softening dollar is, on balance, a tailwind for commodities and emerging markets – a reversal from the dollar dominance of 2022. As history shows, the dollar won’t move in one direction forever. But for now, its downward drift is a welcome relief for many around the world, even as U.S. policymakers keep one eye on its next move.

References

- TradingView — U.S. Dollar Index (TVC:DXY)

https://www.tradingview.com/symbols/TVC-DXY/ - ICE Data Indices — U.S. Dollar Index (DXY)

https://www.theice.com/products/194/US-Dollar-Index-Futures - Visual Capitalist — “Every President’s Impact on the U.S. Dollar”

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/every-presidents-impact-on-the-u-s-dollar/ - Wikipedia — U.S. Dollar Index

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Dollar_Index - Federal Reserve History — The Plaza Accord (1985)

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/plaza-accord - Brookings Institution — Dollar Strength and Trade Balances

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-strong-dollar-and-u-s-trade-balances/ - IMF — World Economic Outlook 2025

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)